Hare-brained History Volume 53: The Vikings

Featuring Uncle Bob, that hottie Freya, Chris Hemsworth, Berserkers, Saint Aidan, Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, and the Battle of Hastings

Welcome to the 53rd installment of Hare-brained History, a blog in which your intrepid host will treat you with absurdities, follies, mind-fucks, and everything in between from the world of history. Today, we can wait no longer. It is time.

For one of my biggest supporters, who has been crying out for the Vikings since volume 1, join me on a trip to the land of the ice and snow, from the midnight sun where the hot springs flow.

First things first: where does the word Viking even come from? There is, after all, no place called Vikingland. The most familiar origin is the Old Norse word víkingr, usually translated as “raider” or “pirate.” That term, however, does not actually appear until the 12th century. That is undoubtedly where we get the modern word Viking, but before that point, things get messy. One theory suggests the term comes from the Old English wicing, meaning “sea raider,” itself possibly borrowed from Old Frisian wizing. Another links the word to the Old Norse vika, meaning a sea mile.

Whatever you want to call them, the Vikings were raiders, traders, colonizers, and warriors of the Norse people of Scandinavia. The Norse themselves were part of a much larger family: the Germanic peoples, of whom there were a whole fucking bunch. These were loosely related tribal societies with similar languages and cultural patterns during the Betty Crocker time.

The Romans were the first to write extensively about the Germani, whom they described as barbarian savages living beyond the Rhine. This portrayal was exaggerated, as Roman portrayals of outsiders usually were. Rome fought the Germanic peoples throughout the Western Roman Empire. Their catastrophic defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9, yes, literally the year 9, ensured that the region we now call Germany would never be fully conquered. It remained outside Roman control, though heavily influenced by Roman culture.

Elsewhere, Germanic peoples followed very different paths. The Franks and other groups in Gaul came under Roman rule and eventually became the backbone of what is now France. Migratory Germanic groups such as the Goths and Vandals, originating in Eastern Europe, were driven westward by war and pressure, and ultimately carved out kingdoms in Italy, Spain, and North Africa. These groups converted to Christianity relatively early and played central roles in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

Meanwhile, the Saxons, along with the Angles and Jutes (never forget the Jutes), crossed into Britain in the 5th century, forming Anglo-Saxon England. At the same time, the North Germanic peoples moved north into what became Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. In the process, they pushed the Sámi, Uralic-speaking peoples who had inhabited the region, into the Arctic reaches of Scandinavia. The Finns, also Uralic speakers, arrived later and were a Baltic people, which makes Finnish linguistically closer to Hungarian and Estonian than to any Scandinavian language.

What much of Europe Christianized relatively early, these groups did not. The Anglo-Saxons in England, the Norse in Scandinavia, and the Finns and Sámi all retained their religious traditions long after the rest of Europe had converted. It is from this pagan North Germanic world that “the Vikings” emerged. I wrote almost all of that myself with only marginal help from research. Are you proud of me, Uncle Bob?

The Old Norse religion was, in many ways, similar to the ancient Greek and Roman religions: a polytheistic pantheon of gods and goddesses who took an active interest in, and had real power over, the everyday world. The Norse imagined existence centered on the great world tree Yggdrasil. At its heart, the Gods gathered to conduct their thing, literally, their governing assembly. Around Yggdrasil existed nine worlds, including Midgard, where humans lived.

The Norse gods were divided into two groups, the Æsir and the Vanir; the precise difference between them is unclear to me, and frankly, it seems to have been unclear to them as well. The two groups fought each other until they realized it was pointless, at which point they made peace. Among the most powerful of the gods was Odin, the one-eyed, long-bearded Allfather, who helped create the world by slaying the primordial being Ymir and gave life to the first humans. Odin was widely regarded as the god of the dead and of warfare, two essential Norse activities. Please hold.

Odin received slain warriors in Valhǫll, the “Hall of the Slain,” better known as Valhalla, one of several possible destinations for the dead. Another was Fólkvangr, a similarly pleasant afterlife presided over by the goddess Freyja, a hottie deity of sex, love, beauty, and also, once again, war. I am unsure why Valhalla receives all the attention. There was also Hel, ruled by the goddess Hel, which I am going to assume was less good, and Rán, which I am also going to assume was less good. And then there was the burial mound, which is where I presume the normies went.

The other most important god was, of course, Thor, son of Odin, the hammer-wielding god of thunder, storms, strength, protection, fertility, farmers, and free people, played by Chris Hemsworth. The Norse world was also populated by a variety of mythological beings: dwarves, elves, landvættir (nature spirits similar to nymphs), and the Jötunn, a race of giants whose male members were often called trolls, which tells you everything you need to know.

For the Norse, death was not something to be feared, especially death in battle. Those who died gloriously could expect to feast alongside Odin or Freyja, preparing for Ragnarök, the end of the world, when the dead and the gods would fight together against demons and giants. After that, the world would be destroyed and reborn. So yes, suffice it to say, they were a warlike people. Below is Freya.

What propelled the Vikings is a difficult question to answer, mainly because “the Vikings” were not a single people with a single motivation. They were a loose collection of Norse peoples, driven by different forces: trade, colonization, exploration, prestige, and raiding. What united them was the sea. Their mastery of shipbuilding made all of this possible. They constructed langskips, longships powered by both oar and sail, with long, narrow hulls ranging roughly from 45 to 75 feet, built from overlapping oak planks riveted together. This made them sturdy yet flexible. The narrow draft allowed them to skim shallow seas and slip far inland along rivers, while still surviving rough open ocean voyages. Few societies on Earth were as mobile as the Norse.

Broadly speaking, overpopulation played a role. Scandinavia is, you might be surprised to learn, very cold, mountainous, and agriculturally unforgiving. Arable land was scarce, and as populations grew, pressure mounted. People were pushed outward, often violently, in search of food, wealth, and opportunity. There was also a demographic imbalance. Early Norse societies practiced female infanticide at higher rates, which created a shortage of women, which is bad. Raids could bring captives, status, and marriage prospects. Some Vikings returned home with loot; others stayed, settling permanently in conquered regions. Still others fled persecution or political consolidation at home.

In Denmark, the Danes, a Germanic people centered on Jutland, began centralizing power in the early eighth century. They organized the earliest large-scale raids, and became the first Christianized Norse kingdom under King Harald Bluetooth, so named, allegedly, for his earpiece. In Norway, power coalesced under Harald Fairhair, who, according to the sagas, ruled from roughly 872 to 930. Much of what we know comes from sagas, unreliable but wonderful blends of history, folklore, and myth. Harald’s rise displaced rival clans, who then fanned outward, colonizing the Orkney Islands, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland.

The Swedes and the Gutar of Gotland were doing their own thing. While Sweden lacked an early unified monarchy, Swedish Vikings dominated the Baltic and pushed eastward. They sailed down the Dnieper River to Kiev, where they helped establish Kievan Rus, a predecessor of modern Russia. Some went even farther, reaching Constantinople. The Eastern Roman emperor Theophilos, impressed by their martial skill, recruited them as his personal bodyguards, forming the Varangian Guard, an elite unit composed of Norsemen and later Norse-descended Rus. The Varangian Guard.

Technology helped propel them forward. Their ships were unmatched, but so too was their metallurgy. Scandinavia was rich in iron ore, allowing for high-quality weapons and armor. Religion may also have played a role. Raiding Christian monasteries and cities may not only have been profitable but retaliatory. And then there was social structure. Norse society was rigidly hierarchical. At the top were the jarlar, aristocratic chieftains who controlled land, politics, and warfare. Beneath them were the karlar, free men, farmers and workers who could be called to arms. At the bottom were the thralls, enslaved people captured or purchased, essential to construction, agriculture, and domestic life. Thralls were disposable. In some cases, they were burned alive alongside their master at his funeral.

Women, or at least free women, occupied an unusual position by medieval standards. While not equal to men, Norse women had more rights than their Christian counterparts. They could own property, inherit wealth, initiate divorce, and wield religious authority. They controlled the household by law. Norse women lived longer than men and longer than Christian women. After Christianization, not only did these rights erode, but female life expectancy dropped as well. The legendary shieldmaidens remain debated, but archaeological evidence suggests that some women did fight, at least occasionally.

As for what the Vikings looked like, much like modern Scandinavians: generally fair-skinned, with hair that could be blond, dark, or red. Blondes were more common in Sweden; red hair was more common in Norway. Men wore their hair and beards long, though warriors tended to keep theirs shorter for practical reasons. Some men dyed their hair with saffron to appear golden. Women braided their hair, and wealth was displayed through clothing and jewelry: silk, brooches, arm rings, belt buckles, and necklaces engraved with runes and religious symbols.

All free Norse men were required to own weapons and could carry them openly. Jarls possessed full kits of helmets, shields, mail, and swords, though swords were expensive and often symbolic. Axes and spears were the weapons of choice. Violence permeated Norse society. In Norway, skeletal remains show that roughly 72 percent of adult male bodies bore weapon-related injuries. Even after unification, Norway remained deeply violent, while the more centralized Danish kingdom experienced less internal bloodshed.

And here come the berserkers, Uncle Bob. Berserkers were elite warriors said to enter trance-like battle frenzies. Their name comes from Old Norse ber and serkr, “bear-shirt,” as they wore bear skins. Their counterparts, the ulfheðnar, wore wolf skins. They likely consumed psychoactive substances before battle. A poem honoring Harald Fairhair describes them:

I’ll ask of the berserks, you tasters of blood,

Those intrepid heroes, how are they treated,

Those who wade out into battle?

Wolf-skinned they are called. In battle

They bear bloody shields.

Red with blood are their spears when they come to fight.

And no, Vikings did not wear horned helmets. That is anachronistic bullshit. Do not let yourself be deceived.

We have wandered, I know. They kept poor records, and I am riffing. But perhaps the most significant force driving the Viking Age was the presence of wealthy, divided, and poorly defended lands within range of their ships, and the Vikings had the means to reach them.

The so-called Age of the Vikings is traditionally said to have begun in 793, Alexandra Daddario. On the island of Lindisfarne, off the coast of what is now Northumberland, in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, a monastery was founded in 635 by, believe it or not, Saint Aidan. Not this Aidan, I can assure you. Lindisfarne was a center of learning, wealth, and religious authority in early Anglo-Saxon England, and that made it a tempting target.

On June 8, 793, a Viking longship appeared offshore and caught the monastery completely off guard. Monks were slaughtered, some thrown into the sea, others carried off as thralls. The monastery was stripped of its wealth, and its sacred relics were desecrated. The shock was immediate and profound. Alcuin of York, a Northumbrian scholar writing shortly after the attack, lamented:

“Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race… The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God.”

The raid sent shockwaves throughout Christian England. While Lindisfarne survived the initial attack, it was abandoned less than a century later due to repeated Viking raids. From this point on, the histories of England, Ireland, and Scotland would be permanently marked by the Norse. By 853, a Viking leader became the first King of Dublin, establishing a powerful Norse kingdom. Over the next two centuries, Irish kings fought intermittently against Viking dominance on the island. It was not until Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, King of Mide, and Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, mercifully remembered as Brian Boru, King of Munster, began working together that the Dublin Vikings could no longer “single-handedly threaten the power of the greatest kings of Ireland.”

Brian Boru eventually became High King of Ireland, with Máel Sechnaill’s acknowledgement. He met his end in 1014 at the Battle of Clontarf, where his forces defeated the Dublin Vikings and the treacherous Leinstermen. Brian himself was killed in his tent after the battle, an old man who had nonetheless reshaped Ireland.

The Vikings also made deep incursions into Scotland, establishing the Kingdom of Orkney and the Kingdom of the Isles in the Hebrides, usually under Norwegian overlordship, except for the frequent occasions when they rebelled. The Welsh, incidentally, were among the most successful at resisting Viking settlement altogether. Gwlad, gwlad, pleidiol wyf i’m gwlad.

We will return to England. Below is the death of Brian Boru.

Truly, anywhere in Europe connected to water was at risk of a Viking incursion. The Norse traveled down through rivers and through the Black Sea, establishing Kievan Rus and serving as mercenaries for the Byzantines, as we have seen. They raided across the Baltic, along the Pomeranian coast (that’s Germany, not little dogs), and the Low Countries. In 842, Vikings even began raiding into Spain, operating from a base near the mouth of the Loire, striking at Muslim-held al-Andalus over the following centuries. A dozen Viking longships appeared in the Mar da Palha in Portugal, plundering what we now know as Lisbon, then under Islamic rule. The Andalusi chronicler Ibn Hayyān recorded the encounter:

“At the end of the year 229/844, the ships of the Norsemen, who were known in al-Andalus as majus, appeared off the western coast of al-Andalus, landing at Lisbon, their first point of entry to the forbidden lands. It was a Wednesday, the first day of Dhu al-Hijjah in that year, and they remained there thirteen days, during which time they engaged in three battles with the Muslims.”

But the Vikings also looked west. From their settlement in Iceland, according to the Icelandic sagas, which I have read, and that is not a lie, Erik the Red was exiled from Icelandic society after a chain of events involving thralls, a landslide on his neighbor Valthjof’s land, retaliation by Eyjolf the Foul (so named because of his breath), and a series of killings that, to me at least, seem entirely reasonable from Erik’s perspective. Erik killed Eyjolf, but because Eyjolf was a free man and thralls were considered less than men, Erik was sentenced to three years of exile.

During that exile, Erik and his companions became the first Norse to sail to and settle Greenland. Three communities emerged along the sheltered fjords of the southwestern coast, imaginatively named the Eastern, Middle, and Western Settlements. At their height, these colonies supported over a thousand people living largely pastoral lives, until climate conditions deteriorated during the Little Ice Age.

Erik’s son, aptly named Leif Erikson, looked even farther west. According to the sagas, Leif was blown off course while sailing to Greenland and discovered Vinland, a new land beyond the western sea. He established a small settlement before returning home upon learning of his father’s death. While the sagas themselves are literary rather than strictly historical, we know for certain that Vikings did reach North America. Archaeological evidence at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland confirms a Norse settlement dated between 990 and 1050, with tree-ring evidence pinpointing activity to 1021, all of which aligns remarkably well with the saga tradition surrounding Leif Erikson.

Throughout the ninth century, Francia was repeatedly raided by Viking fleets along its coasts and up its great rivers, especially the Seine and the Loire, allowing raiders to strike deep inland. Paris was besieged twice, and twice it held out, including the brutal siege of 885–886, which dragged on for nearly two years. One of the Viking leaders involved in that siege was Rollo, known as either “the Dane” or “the Walker,” the latter because he was very keenly aware of his cardiovascular health. Rollo was the most dangerous raider in Francia and for the next twenty-five years, he ravaged the region until his defeat at the siege of Chartres. There, the Franks made a deal. In exchange for baptism, loyalty to the Frankish king, and a pledge to defend the Seine from further Viking incursions, Rollo was named Count of Rouen, effectively founding what would become the Duchy of Normandy, a name derived from Normanni, “men of the North.” Rollo spent the final two decades of his life as its ruler.

From this settlement emerged a distinct Norman culture. Through conversion, settlement, and intermarriage, the Normans became, as one chronicler put it, “not only Christians, but in all essentials Frenchmen.” Yet they retained their martial edge. While no longer raiding France, Norman second sons and adventurers would carve out kingdoms in southern Italy and Sicily, serve as mercenaries and crusaders across the Mediterranean, and, in time, one Duke of Normandy would press his claim to a foreign crown, reshaping the course of European history. Below is a historical picture of Rollo.

Following the raid on Saint Aidan’s, Viking attacks continued in sporadic groups for the next sixty years in England. Then, in 865, the Great Heathen Army landed in force, traditionally associated with the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok. Over the next thirteen years, the army swept across Anglo-Saxon England, conquering petty kingdoms. The total conquest was prevented only by King Alfred the Great, who defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Edington. The resulting treaty formalized Viking control over much of northern and eastern England, a region that became known as the Danelaw.

Conflict between the Viking Danelaw and Anglo-Saxon England continued for generations. Tensions reached a climax on November 13, 1002, when King Æthelred II ordered the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, a mass killing of Danes living in England. Unsurprisingly, the Danes did not like this. In response, King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark and Norway, so named because he decorated his beard with forks, launched a full-scale invasion. Sweyn, an able and ambitious ruler, defeated Æthelred and briefly became King of England before his death.

Sweyn’s son, Cnut the Great, succeeded his father, and for seventeen years, Cnut ruled an empire stretching across England, Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden, a domain later called the North Sea Empire. Cnut himself styled his title with charming precision as “King of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes.” A medieval historian described him as “the most effective king in Anglo-Saxon history.” After Cnut’s line failed, the throne returned to the House of Wessex with Edward the Confessor, Æthelred’s son.

Edward had spent much of his early life in exile in Normandy, and his reign reflected this upbringing, a source of tension among the Anglo-Saxon nobility. Edward was deeply religious and would later be canonized, remembered as a pious and largely well-intentioned king. Crucially, he had no children, and even before his death, powerful factions were circling. Chief among them was the House of Godwin, whose patriarch, Godwin of Wessex, had long opposed Edward before reconciling through marriage. When Edward died on January 5, 1066, he left no clear heir. Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex and Edward’s brother-in-law, claimed that Edward had named him successor on his deathbed. Backed by the Witan, the council of Anglo-Saxon nobles, Harold was crowned king. His rule, however, was immediately challenged by two formidable rivals.

The first was Harald III of Norway, better known as Harald Hardrada, the “Thunderbolt of the North.” At fifty-one, Harald was a towering figure both literally and figuratively. He had spent his youth as a mercenary in Kievan Rus and as commander of the Varangian Guard in Constantinople. Described as larger and stronger than most men, with massive hands and feet and a distinctive long upper beard, Harald was every inch the Viking. Yet he was also a rare polymath: a skilled brewer, swimmer, skier, and an accomplished poet. His claim to England was tenuous, but like a true Viking, he intended to take what he believed was his by force.

The second claimant was William, Duke of Normandy, derisively known as William the Bastard, the illegitimate son of the previous duke. Born in 1028, William inherited the duchy at just seven years old and spent his childhood in constant danger as Norman nobles fought for power. By nineteen, he began to assert control, and his marriage to Matilda of Flanders secured a crucial alliance. William was a formidable figure: around 1.78 meters (5 foot 10), tall for his time, and renowned as a fighter and horseman. Unlike Harald, he cared little for poetry, but he was devout, and his marriage was unusually loving and faithful by medieval standards.

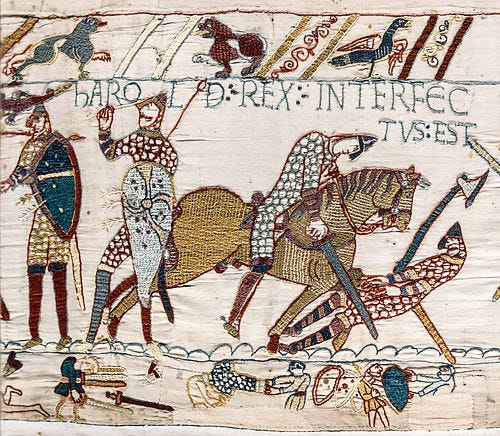

William’s claim may, in hindsight, have been the strongest. Edward the Confessor had known him well during his Norman exile, and William insisted Edward had promised him the throne. He further claimed that Harold Godwinson himself had sworn to support that claim. Whether this oath truly occurred remains unclear, but by 1066, the die was cast. All three men prepared for war: Harold consolidating power in England, Harald Hardrada gathering his warriors, and William assembling a fleet. Edward the Confessor in the Bayeux Tapestry.

King Harold first secured the loyalty of two powerful earls through marriage alliances, but almost immediately his reign was challenged to the north. Harold’s exiled brother Tostig, whom I neglected to mention largely because the scholarship surrounding him is so fucking muddled, had allied with Harald Hardrada of Norway. The precise nature of their pact remains unclear, not least because Tostig himself also claimed the English throne. Whatever the details, the result was clear enough: invasion.

In September 1066, roughly 10,000 troops from Norway, the Earldom of Orkney, and the Kingdom of the Isles landed in North Yorkshire, all Viking strongholds. On September 20, Harald and Tostig defeated the Earls of Northumbria and Mercia at the Battle of Fulford, then marched south, expecting to face little resistance. What they did not expect was Harold Godwinson.

Having learned of the invasion, Harold gathered his men and marched from London to Yorkshire, a distance of 185 miles (298 kilometers), day and night, in just four days. On September 25, the Norwegians were caught off guard. As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records, “Harold, king of the English, came upon them beyond the bridge by surprise; and there they joined battle and fought very hard long in the day.” At Stamford Bridge, home of Chelsea Football Club, over the River Derwent, battle was joined.

Legend holds that the English advance across the bridge was delayed by a single Viking wielding an axe, who cut down more than forty Englishmen before being killed when a soldier crept beneath the bridge and stabbed him with a spear through the planks, right into his balls. However it happened, the Norse army collapsed. Harald Hardrada was killed by an arrow to the throat, Tostig fell in the fighting, and the Norwegian force was so utterly destroyed that only 24 of the original 300 ships were needed to carry the survivors home. It was a crushing victory. Three days later, the Norman fleet landed in Sussex.

Exhausted but with no choice, Harold turned his army south. As he marched, he gathered additional troops, while William of Normandy established a beachhead and advanced to a position roughly seven miles north of Hastings. William drew up his army carefully: Bretons on the left, Normans in the center, and French allies on the right. Harold arrived on the night of October 13 and took up a strong defensive position on the hills of Senlac and Telham.

Numbers vary, but both armies likely fielded fewer than 10,000 men, roughly equal in size. At 9 a.m. on Saturday, October 14th, 1066, the Battle of Hastings began. Norman archers fired uphill at the English shield wall with little effect. The English, lacking archers, returned little fire. Spearmen were sent uphill and driven back, followed by infantry and cavalry, also repulsed. Then a rumor spread that William had been killed, and the Norman army began to falter.

Sensing an opportunity, Harold ordered his men forward. William rode among his troops, lifted his helmet to show he lived, and personally rallied them before launching a counterattack that drove the English back up the slope. A lull followed in the early afternoon, rest and snacks being taken. William needed a new approach. He ordered feigned retreats, drawing portions of the English line downhill, where they were cut to pieces when the Normans turned back. Even so, the English position held. William is said to have had two or three horses killed beneath him during the fighting. By late afternoon, the battle seemed headed toward a stalemate until fate intervened. King Harold Godwinson was killed, traditionally said to have been struck by an arrow in the eye. However it happened, the effect was decisive. Leaderless, the English army broke.

Although resistance and rebellion persisted for years, William was crowned King of England on Christmas Day, 1066. The Norman duke, himself a descendant of Vikings, established the House of Normandy and reshaped England forever. William the Conqueror is often remembered as the founder of England as we know it. The death of Harold in the Bayeux Tapestry.

While the defeat of Harald Hardrada is often said to mark the end of the Viking Age, it did not mark the end of Viking influence. William the Conqueror, a direct descendant of Rollo, reshaped English history forever. Viking descendants ruled in Normandy, carved out kingdoms in southern Italy and Sicily, established themselves across the Baltic, and laid the foundations of states in Ukraine and Russia. Their impact on Europe cannot be overstated. They settled, intermarried, traded, enslaved, converted, and governed. The movement of people, willingly or otherwise, profoundly altered the genetic, cultural, and political makeup of Europe.

Over time, Vikings were remembered less as complex human societies and more as crude savages, much as their Germanic ancestors had been caricatured by Roman writers. That image shifted again during the Romantic era of the late 18th and 19th centuries, when Norse mythology was rediscovered and reimagined across Europe, particularly in Germany and England. The operas of Richard Wagner, steeped in Nordic myth, helped cement a heroic vision of the Norse, one that would later be cynically appropriated by the Nazis and by modern neo-Nazis as well.

The Vikings were neither heroes nor villains. They were a product of their time. Some were brutal raiders, some were daring explorers, some were farmers, traders, poets, kings, and mercenaries, and many were all of the above. What matters is that they helped shape the course of European history, and as Europe went on, for better and worse, to shape much of the world, the legacy of the Vikings went with it.

So what have we learned? Mainly, that this writer rewards his paid subscribers. Become one, and I promise to write whatever you want, provided you’re patient with me. Are you happy now, Uncle Bob?

Note: Thank you for making it to the end! What began as a farcical blog for a depressed, history-loving nerd to mess around with, an escape from the hole I’d dug, has grown into something more. As I’ve said before, this was always meant to be entertaining rather than academic. I’m not doing the deep-dive research that kept me from pursuing a career in history, but the work I put in here is careful, thoughtful, and, yes, work. And while it often doesn’t feel like work because I love it, it still takes time and effort. So if you’ve enjoyed this, please consider tossing a few bucks my way. My goal is to make history both educational and entertaining, the kind of history that first captured my imagination as a kid. Thank you for reading, and thank you for coming along on this journey. If you’ve made it this far, just know, I love you.

This was so interesting and the berserker fact is insanely cool. If you wrote all my uni reading I’d devour it 🙏

You got the origin of the Irish. Many miss that.